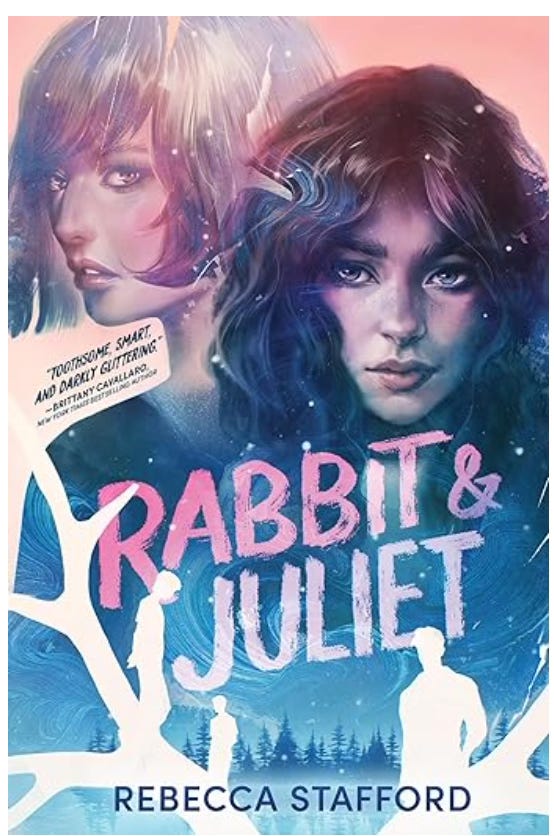

Last month, which feels like eleventy billion years1 ago, I ran a Q-and-A with my friend/colleague Desirée Zamorano about her newly published novel. This month, I’m featuring Rebecca Stafford, who published her first YA novel, Rabbit & Juliet, a week ago.

As it happens, Rebecca, Desirée and I had a DIY (DIO?) writing retreat in New Orleans in May 2022. We took it very seriously, finding quiet places to work throughout the morning, meeting up for lunch, where we might discuss another writer’s essay or share our pages, then working through the afternoon. Perhaps it’s entirely incidental that they’re both publishing in the fall of 2024; I no longer remember what they were working on that spring. But, not to get all Virginia Woolf on you, I do believe writers, especially women, need not only rooms, but retreats. And if you can’t get into places like MacDowell or Yaddo (and I can’t, but Rebecca and Desirée have more serious cred)2, then you need to create these opportunities for yourself, somehow, some way.

Rebecca is a kick-ass poet, and with Rabbit & Juliet, she proves she’s a kick-ass novelist, too. She also has great hair. And yet, despite her abundance of gifts — it seems all the good fairies came to her christening — I still love her. Her answers to my questions are incredibly/inevitably wise and generous, helpful to new and old writers.

Q: You're a prize-winning poet under the name Rebecca Hazelton Why did you decide to write YA?

There are a number of reasons. One reason is that when I lived in Madison, Wisconsin, I was neighbors with Brittany Cavallaro. We met as poets and I was with her as she began to draft the Charlotte Holmes Series. So essentially, I had seen it could be done. Despite her encouragement, it took me many years to make a serious stab at it. I liked the idea of being a novelist more than actually sticking to the task, which I think is a pretty common experience for anyone who wants to write a book.

The other reason is more complicated, and unflattering. If you believe what people tell you matters, I’d done well as a poet. But no matter how hard I worked or how many gold stars I received, my work and my accomplishments were always lacking when I compared myself to others. This sounds very “poor me, it was so hard to be successful,” but what I’m trying to say is that you can't build a self out of external validation, and I had tried to do just that. The results were what you’d expect – soul curdling. I wanted to be happy for people when they got book deals and won contests and published in great journals; instead I felt envy.

I suspect your readers are now thoroughly appalled, so let me tell you how I have (mostly) pulled myself out of this ugliness. I decided to stop engaging with the business of poetry for a while, and to put my creative efforts elsewhere. Novel writing was so far outside my skills set, I was confident it would help me disrupt my habits of writing and thinking. Writing a novel allowed me to sidestep my own expectations, as well as anyone else’s. It was uncomfortable and humbling, but it also let me play again, and fail, and start over.

All of that is a long-winded way of saying that writing YA gave me some sorely needed joy. I needed to remember why I liked writing, to become more attuned to the act of creation and less worried about its reception. I have a new poetry book, Generic Husband3, coming out in 2025 with Louisiana State University Press. We’ll see if my newfound perspective holds up when that happens! I doubt I’m cured of all my insecurities. But I’m hopeful I’ve improved at least.

I don’t visit Goodreads, though.

Q: What were the seminal YA reads of your reading life? Do you still read YA for pleasure, as many adults do? (Reminder, this question comes from someone who is currently re-reading the Noel Streatfeild "shoe" books.)

I remember loving The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley, and Sabriel by Garth Nix. I also remember being utterly drawn in by a book called Fog by Caroline B. Cooney, which was full of trauma, mental illness, and abuse. The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers was a book that meant a lot to me at the time. Looking back, it’s obvious why that book would have appeal – it easily lends itself to a queer reading. There were also a number of books in the Christopher Pike or R.L.Stine camp that I enjoyed, but I can’t remember their names, just that they were full of murder and madness.

In school, we passed around Judy Bloom’s Forever to read the sex scenes (I remember something about not putting cologne on a sensitive organ, and I learned that lesson and have never done so) but I don’t know if I read the full book. The same thing happened with a bathtub scene in Pet Sematary, and I shudder to think what that did to my burgeoning sexuality.

I desperately wanted the Weetzie Bat series by Francesca Lia Block but for some reason never got my hands on them. I still haven’t read them. They remain deeply cool and unknowable, a California fever dream I’ll never touch.

Mostly, though, I read adult fiction as a teen, which means I missed out on classic YA like The Outsiders, which I only read recently and adored. In my twenties I read the big YA books like the Twilight series and The Hunger Games. I discovered Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle4, which I think is overlooked but so sensitive and fantastic at showing a teenager’s interior life. But the YA book that really shook me was Courtney Summer’s Sadie. I remember finishing it and thinking, “You can do that in YA?” That book really made me want to write.

I do read YA for pleasure, although I’m also a regular reader of adult sci-fi and fantasy. I just finished Neil Schusterman’s Scythe series; it was excellent. I really enjoy Riley Redgate’s YA novels, which I think are so sensitive, fun, and do interesting things with class and race. Mindy McGinnis is great and her latest, Under this Red Rock, is chilling. I’m not sure if Naomi Novik’s Scholomance series is classified as YA, but it’s fantastic.

Q: This may sound odd, but for novelists such as myself, who don't/can't write poetry, it's a slightly mysterious art. How does being a poet inform a novel? Are the processes different?

Poetry favors the micro, which it uses to gesture at something larger. As a poet, I’m comfortable with word choice, sentences, and rhetorical turns, at using a few words to maximum effect. Since even a long poem is a tiny scrap compared to a novel, the rhetorical movement of a poem is so much more immediately apparent to me than when I am writing prose. I’m not saying I know how a poem will end when I start – that would result in a pretty dull poem I think – but I’ve got a clear sense of the possibilities. Some of that is due to experience, and some of it is because poems have inherent arguments, even if they aren’t in the shape or form that we typically think of when we hear that term. For example, an elegy might argue that memory can triumph over death, or that there is no consolation, or that God does or doesn’t see our loss.

All of those poetry skills are useful when writing a novel, but there’s a radical shift in focus moving from poetry to prose because of the sheer size of the project. I can’t tell from my first sentence where we are going like I can with a poem. Instead, I’m in a forest, trying to hack my way through, with no map or aerial view. The path I’m carving out might be leading me through, or doubling back on itself, or ending precipitously. If I keep going with this metaphor, writing a novel is much more likely to end with me in a ravine with a broken leg.

Q: How long did it take you to write Rabbit & Juliet? What, if anything, was unexpected?

It took me about four years, but that was because I am a teacher and I wrote mostly during summers. It went through about three drafts, I think, before I started sharing it with people, and then I revised it more before sending it out to agents.

The most unexpected thing for me was that I finished it! I’d tried and failed several times, but there was something different about this attempt than the others. I really went into it like it was a thought experiment. I believed it would help me talk to my students about writing, and maybe about the process of getting an agent. I was entirely unprepared to complete it, to get an agent, or to get a deal. None of that had really occurred to me, and in fact when my agent had her first call with me, clearly to offer me representation, I had to explicitly ask her if that was what was happening because I hadn’t let myself really consider it could happen. I’m sure she got off the phone thinking I was a bit dense.

Q: You're a professor at North Central College in Illinois: What have you learned from your students?

When I was younger, both as a writer and a person, I thought I knew what made writing good. As I age, I realize that “good" is just a placeholder for so many assumptions about who gets to write, in what way, what they can say. When we read together, my students notice things I miss, make connections I wouldn't have considered, and react emotionally in surprising ways. Ultimately, engaging with their points of view and what matters to them as artists makes me more flexible in my thinking.

Likewise, it’s easy as a practiced writer to become habitual in your singular way of doing things – understandably so, since our regular “moves” are hard won efficiencies – but new writers try things just to try. They don’t know or don’t care that they can fail, which is a good reminder to me that success isn’t just a completed work. It’s all the missteps along the way.

Q: Do you have an elevator pitch for R&J?

Honestly, I’m terrible at talking about my work, and I’ve struggled with this very question since I first started writing. But here’s my best shot:

A sad, queer girl kisses a bad, queer girl and they beat up sexual predators.5

Q: Did you have a dream reader in mind for R&J? (It could be a real-life person or just a general ideal).

My dream reader is basically myself at sixteen. I grew up in a small town during the 90s in the deep south. Being queer didn’t feel safe or welcome. I felt trapped, tamped down, and angry about the many ways being a girl limited my options. I do think things are better now, but I wrote the book I wanted to read back then, one where you could kiss a girl and then kick a guy’s ass for being a creep.

Q: Which feels more "naked" as a writer, poetry or fiction? Whatever your answer, how did that affect R&J?

Everyone has a different approach, I’m sure, but I write from a place of intimacy and discomfort. The ugliness of our feelings interests me as much or more than our better natures. So writing poetry and fiction are equally vulnerable acts. Even when I write in persona in a poem, or as a character in a book, I feel as though I am that person as I write. The voice is a construction, but the emotions behind it are real, even if they aren’t necessarily “true” to my own experience.

For example, to get into Rabbit’s voice, I ended up dictating portions of the book, speaking her words out loud using speech-to-text. In a sense I had to become her, to let her talk through me, to understand what she needed to do. She’s not me – but I felt like I was her at times.

Q: You have a full-time job, you're a parent to a child in grade-school -- I kinda hate this question, because it has some patriarchal undertones -- but how do you get things done?

I don’t! Or rather, I have, but it was at a cost. Writing Rabbit and Juliet while working full-time as a teacher and trying to be present for my child as a parent really wore me down. I had a lot to learn, and I couldn't find free time to practice novel writing. Or rather, if the time was there, I was exhausted. I was also quite ill during that time. It's why it took me four years to write the book; I really could only write it seriously during the summers because I didn't have the focus or the energy when I was working. If I was writing, I was neglecting other parts of my life. And I love my students, and I love my family, so more often than not it was the writing I sidelined in favor of them.

Recently, I was diagnosed with ADHD. Now that I'm on medication, everything feels so much easier. It's not that my workload is magically better, but I can finally understand where I need to put my energy and how much is a reasonable amount of effort for the results I want. Drafting the next book is already going significantly faster, so I’m hopeful it won’t take another four years!

Q: And on top of everything else -- you had long Covid. How did that affect your writing -- and your life?

It changed my life in every way. I fell ill with COVID-19 early in the pandemic, before vaccines. I had serious pneumonia, brain fog, extreme fatigue, and body aches. I spent what felt like a year on my couch. My world became very small. And then there were the drugs, their side effects, the sense that nothing would ever get better. Things did improve, but with agonizing slowness. At this point, I’d say I’m 95%, and I’m so grateful that I can do things like shop for groceries, cook, and walk in my neighborhood. I can chase my child, and while I get more out of breath than I feel I should, I can still do it, I can still run. That was impossible for a long time.

I mentioned earlier that I dictated portions of the novel to get into Rabbit’s voice. I also used that method because at the time I was on a drug that made my hands floppy. I had difficulty typing, or even holding my phone. But I could hit the speech-to-text button and talk.

Strangely, and I cannot explain this, I could dictate even though I struggled with speaking to others. In my conversations, I would lose words and my brain was sluggish. I would try to say “put that on the table,” be unable to find the word “table,” and end up saying something like “put that on the thing, the thing with legs.” It was incredibly upsetting. But when I was dictating, I was composing, and somehow compositional language – writing in the air – was accessible to me. The words came easily, and the sentences were clear. It truly felt as though writing existed in a different part of my brain.

Q: I taught a little at the college level years ago, but now when I teach, it tends to be adults, often people past retirement age. I know what advice I give them, but I'm curious about what you tell your students about the writing life. Do you give them practical advice?

I do give some practical advice, with the caveat that what works for me doesn’t necessarily work for everyone.

Examining your habits is very helpful. You might try a different method of writing (by hand, for instance), or change up the conditions of how and when you write.

I advocate for taking walks when you are stuck. Just let your body move and see if your brain can work out some things in the background. If nothing else, you’ll probably feel better.

You need writer friends who will tell you what you don’t want to hear, but with kindness.

Try to figure out what success means to you as a writer, not whatever the popular conception of writerly success is.

Send poems/stories out to ten journals. If it’s a no from all of them, revise. Then send out again.

Consider whether the events in your book are happening because they need to, or because you want them to. Can you trace their causes backwards?

Read your poems aloud, over and over. With every iteration, you will get more and more tired of saying the weaker lines. Trim until you aren’t annoyed. This also works for prose, but I’d hold off until you are very far along, otherwise you will unwrite your book as you go, like Penelope at the loom.

Read your dialogue aloud and try to imagine a real human speaking this way.

Q: Can you imagine a life without writing? A happy one?

Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if I’d taken art more seriously. There was a time where I loved to paint and draw, and at some point, I don’t know when but I do remember thinking this, I decided I was never going to be a great artist but I could be a great writer. The hubris there is just breathtaking.

The result was that I stopped drawing as much, stopped painting, and eventually devoted myself to writing entirely. What skills I had deteriorated, and soon it felt too late to turn back. I thought that I had to be a genius or I was nothing.

If writing has taught me anything, it's that what we call genius is just aptitude. Aptitude helps in the early stages of an artistic practice, but after that, grit and perseverance matter more. I had some aptitude for art, but I didn’t stick with it. I had some aptitude for writing, and I put in the work. Did I just call myself a genius? Perhaps.6

I applied to MacDowell exactly once; I didn’t make it past the first round. But the fact is, traditional writing retreats don’t work very well for writers who publish every 18-24 months.

I’ve had the chance to read some of these and, go figure, they’re great.

This is a GREAT elevator pitch.

You did and I love you for it. But more importantly — you just made it clear that genius can be achieved with hard work.

I think MacDowell must be afraid of you, your prolific output might scare other writers! xo

This interview was wonderful! I far prefer to hear the struggles and challenges than to hear that everything flowed and was tied up in a neat little bow. Sure that happens sometimes, but art is usually labor, and labor is sweaty and down in the nitty gritty.

Laura - I have the “shoes” books up on my favorite childhood books shelf in my office. They are a perennial favorite. 🩵